The responsibility of living with authenticity

Life lessons in having the courage of your convictions, or being a pitiable shell of a creature.

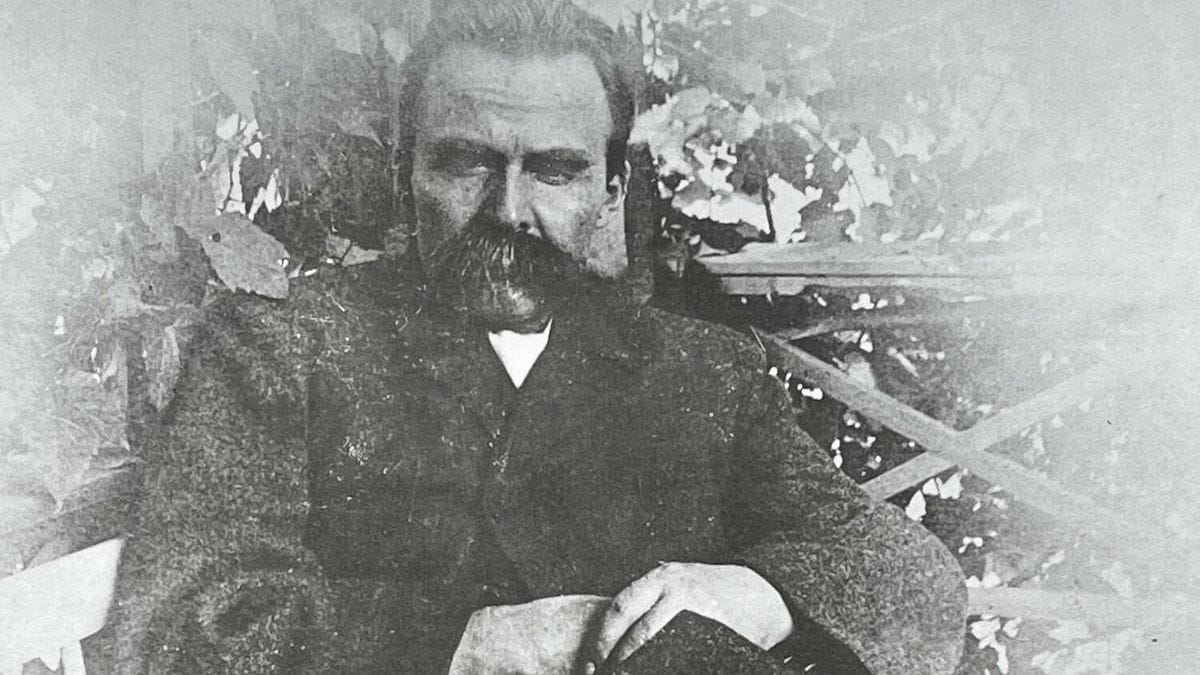

Proto-existentialist philosopher and noted tertiary neurosyphilis connoisseur Friedrich “Incel” Nietzsche was the first modern philosopher to tackle the idea of personal authenticity in one’s approach to life. He distinguished (in German) the terms Wahrheit (truth, veracity) and Warhaetigkeit (truthfulness, veracity) in his Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft (we won’t be translating the title, you can’t be trusted to be serious) as the difference being able to accept the reality of the world and being honest in one’s relation toward it. Many people, including the Nietzschean villain who lives under the imposition of values by society, are capable of recognizing the truth of the world. Only the Nietzschean hero, who seeks to live under his own values, is capable of being truthful with regard to the relation between himself and reality.

As has been stated, Nietzsche’s philosophical development was stymied in a number of ways: proto-Nazi for a sister, falling out with Wagner over Wagner being a proto-Nazi, tertiary neurosyphilis he got during the war, etc. and so on. Thus, it was left to other, later philosophers to turn the basic insights and intuitions of Nietzsche into something respectable as philosophy, so let’s enter three French folks who absolutely fucked each other: Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Around the time of the second world war, Camus, de Beauvoir, and Sartre were of the opinion that modern philosophy had run its course and had nothing new to teach us. After all, the greatest exemplars of modernism, like Marx and Heidegger, had philosophies that led, directly, to global conflict that was soon to turn nuclear and therefore apocalyptic. The (re)discovered earlier works by philosophers like Nietzsche and Edmund Husserl and began working on a new philosophical project that combined the first-person focus of phenomenology with the psychological insights of Freud and Lacan and the sociocultural insights of Nietzsche and Weber. Thus was the philosophy of “existentialism” born.

For Sartre in particular, the concepts of “facticity” and “authenticity” became paramount. One had an ethical duty, under Sartre’s brand of existentialism, to live authentically. That is, like the Nietzschean hero, when one realized that there was no transcendent or universe-imposed meaning or valuation in the world, one had a duty to develop a system of values and live in relation to that system of values such that one’s behavior and attitudes affirmed the truth of one’s chosen values.

Put more simply, when you talk a given talk, you must therefore walk the walk associated with the talk, or Sartre and Camus won’t let you sit at their brasserie table and smoke Gauloises while chasing tail.

In our postmodern world, however, we seem to shy away from authenticity, because it requires a certain amount of courage our herd animal brains resist adopting. To live authentically is, to some degree, to refute the world around you, to reject its values, and to implicitly criticize those who have given in to the facticity of societal values. In other words, most people around you are going to conform to society, and when you deliberately state that it is more ethical not to conform to society but to conform instead to your own chosen values, you are making a value judgment about those who did choose to conform, and it ain’t pretty.

Therefore, many people who are aware of the facticity of the world nevertheless reject or choose not to live authentically, because doing so means some degree of severance from the wider community. If ignorance is bliss and one has the ability to pretend, credibly, to be ignorant, these are the people who would choose feigning ignorance.

We see this in the decision of groups the the BlueSky moderators struggling with whether to ban dickhole provocateur Jesse Singal from the platform.

This space is not to rehash the reasons why Singal sucks. There are plenty of folks who have already written that article better than I could. Nor is it the place to discuss whether, in some ethical sense, BlueSky should preemptively ban him, because I am not interested in persuading you to my way of thinking.

Rather, I am using it as an excuse to highlight a particularly inauthentic brand of cowardice, that of the rule-following moderator.

The rule-following moderator reasons thusly:

I am faced with a difficult decision. If I decide to do α, then there are those X who will criticize me. And if I decide to do ß, there are those Y who will yell at me. Therefore, I am in a dilemma and must look to see what my ruleset Θ says about whether I should choose α or ß.

The moderator therefore offloads the moral weight of her decision onto Θ; whichever she chooses, she may tell X or Y not to be angry with her, but rather to be angry with Θ itself, for it was her desire to follow the rules that led to the decision.

Anyone upset with the moderator should therefore direct their ire not at the moderator’s (perceived) failure in reasoning, but rather to reforming the rules of Θ such that the bad outcome does not occur again.

Going back to our discussion of Sartre at the beginning, we see how this is inauthentic. The moderator is using Θ as a cover for doing what she wanted to do, rather than admitting that she reasoned according to her values and came up with either α or ß.

Personally, I would have more respect for the moderator who, when faced with the difficult choice, identified her values, applied the rule of her values to the problem at issue, and arrived at a given conclusion, and then defended that conclusion than I do someone who tries to make the result one of the facially-neutral application of rules. At least then someone is being honest.

If we were honest with ourselves, we would see that all decisions, even those left up to the cold and unfeeling robotic application of logical rules, are at their base subjective decisions that rely, in no small part, upon our chosen value systems. The decision to follow or not to follow a rule is, at the meta-level, the ethical underpinning of every systemic decision we make. Ultimately, we are the authors and arbiters of our own conduct, and we can either rationally justify that or our reasoning is unable to do so.

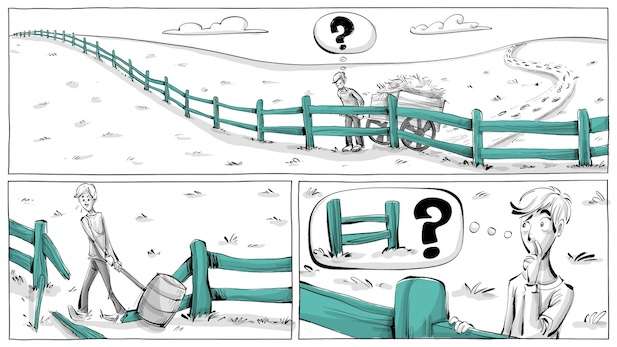

The status quo is a powerful thing. Principled conservatism, as embodied in the metaphor of Chesterton’s Fence, has powerful intuitive (and factual!) appeal. While we all intuit that the current situation isn’t “right,” sometimes foolishly rushing ahead and doing the wrong thing is way worse than doing nothing for now to gain more information or learn more about the situation.

This is especially hard to a thinker keyed into intuitions about justice and righting wrongs, as the impetus to DO SOMETHING can be strong enough to override reason.

But this is not an endorsement of failing to act when action is necessary, either. Sometimes a fence needs to be uprooted and done so yesterday. But the sad fact is that we will never have a perfect, rational system for evaluating which fences to burn down and which to leave up for now. All human reason is going to ultimately underdetermine that task, and we will be left with judgment calls to make.

Some of these we will make correctly. Some we will fail. But we cannot escape the responsibility for trying by abdicating our authenticity to rules. Doing so removes the human at the core of shaping our experience, and when we abandon our humanity in favor of gross quantization, we invariably license atrocity. The authentic way is way more messy and complex, and it may never provide a real solution, but anything else runs the risk of forgetting that the decisions we make are not abstract and will have real consequences upon real lives.