Quit being afraid of postmodernism

You do not know what it is. Your midwit friends do not know what it is. Virtually everything you have ever been told about it is a lie meant to deceive you and keep you enslaved. Stop. Just stop.

Over at Wokal Distance some midwit1 has once again raised the spectre of “postmodernism” in a jeremiad warning of dire consequences to Rationality and The West if this scourge is not banished.

Because I grow ever weary of having this conversation at least two times a year since I began studying philosophy academically 20 years ago, let me attempt to put this nonsense to bed once and for all, by doing it the way only I can: yelling at you all for being idiots.

First, every attempt to define “postmodernism” fails because no one uses that term but people with a desire to criticize a loose group of philosophers they think are threatening them.

It comes from Lyotard’s 1979 book The Post-Modern Condition: A Report of Knowledge, written in French and completely bungled by the Anglophone world.

French intellectuals wanted to know what the effect of the post-60s emergent mass media world was going to be on human knowledge and society, and as the French are wont to do, turned to a wonky intellectual and asked him. Lyotard thought about it, synthesized a bunch of philosophy written in French and German (and therefore relatively unknown to the English-speaking world), and wrote a fairly succinct book about how the answer was “lol I don’t know but nothing fucking good, that’s for sure.”

See, starting in the 18th century and continuing through most of the 19th century, the English-speaking philosophical world thought all decent philosophy was written in English and whatever the French or Germans or Dutch were doing was probably pagan barbarism of the highest degree. Naturally, this kind of thinking infected the American academy, and so a “split” between continental philosophy and “analytic” philosophy was born. Most philosophers today consider this split to be ephemeral, but for a portion of time, it was real.

Lyotard, writing in the 70s, was drawing on the long continental tradition in philosophy, and so many of the thinkers influential to his thought were wholly alien to English-speaking philosophers. A lot of words got used that the English speakers did not understand, and everyone got real scared and did some silly things.2

Lyotard’s ultimate point was that modern media and education were creating a class of people in the “postmodern condition” who were just smart enough to push the button at work that made the widget, but never smart enough to question why or understand the reasoning behind buttons and widgets in the first place. It was not good thing to be in the postmodern condition.

Prior to this, the term “postmodernism” was used primarily to refer to the visual arts, as philosophy had never really passed out of the “modernist” phase. The modernist phase began in the 1500s when thinkers like Rene Descartes began to move away from the “scholastic” philosophy of thinkers like William of Ockham and Jean Buridan, whose learning and theorizing was largely done in concert with the ecclesiastical authorities and monastic life. So-called “modern” philosophy thus sought to supplant reliance on divine revelation with the rediscovery of “reason,” particularly in the thought of Plato and Aristotle.

Modernism continued its development right up until some autistic weirdo named Immanuel Kant revolutionized philosophy by uniting the two main strains of modernist thought (rationalism and empiricism) by showing that neither reason alone nor experience alone were sufficient to generate the totality of human knowledge, and so humanized rationality and universalized experience to the point where we could obtain the necessary certainty of things like causality to ensure a footing for the natural sciences.

The problem here is that post-Kantian philosophy, particularly in Germany, took a very specific route that post-Kantian philosophy, particularly in England, did not. The German tradition became even more humanistic and metaphysical, while the English reaction was to become more logical, abstract, and, well, analytical. Fast forward to the 20th century, and French and German thought was very humanistic, very in tune with the arts, and very much interested in what it meant to be human. The Olympian Rationality, which had dethroned the Titan divine revelation, was itself facing its own Titanomachia as mankind sought once again to philosophize with a hammer.

The great destructive philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, writing at the tail end of the 19th century, took notions like “rationality” and “objectivity” and even those most sacred values we held as Western society to task, exposing them for little more than empty projections of naked self-interest and propagation of extant political authority.

So Lyotard believes we have now turned the tools of modernism against Modernism itself, and the end result being a post-modernist critique of the modernist project. Most continental philosophers considered Karl Marx to be the culmination of all modern philosophy, the last great attempt to systematize a theory of Everything from material conditions. And, famously, in 1914-1921, we saw modernism (and Marxism) fail spectacularly.

For those of us in the vantage point of the 21st century, the idea of Marxism failing so spectacularly seemed weird. But for many intellectuals before the outbreak of the Great War, the idea that Marx was wrong about the material progress of history was strange. Indeed, the world did seem poised for the proletarian revolution Marx foretold, and it was only when the First World War broke out that we saw how very wrong the “scientific” Marxist worldview was.

In the English-speaking (read: anti-Marxist) world, this was met with little more than an a harrumph and puff on a pipe as we considered how to strap more and bigger bombs to planes. In the continent, so ravaged by a type of war we had never dreamed possible, this led to a crisis of faith about the entirety of the modernist project in general.

Some turned away from modernism into nationalism and eventually fascism, deciding that maybe theocratic rule by divinely-appointed emperors was better than law-bound republics, while others became skeptical of “reason” as a tool that led to anything other than trenches and mustard gas and Lewis guns.

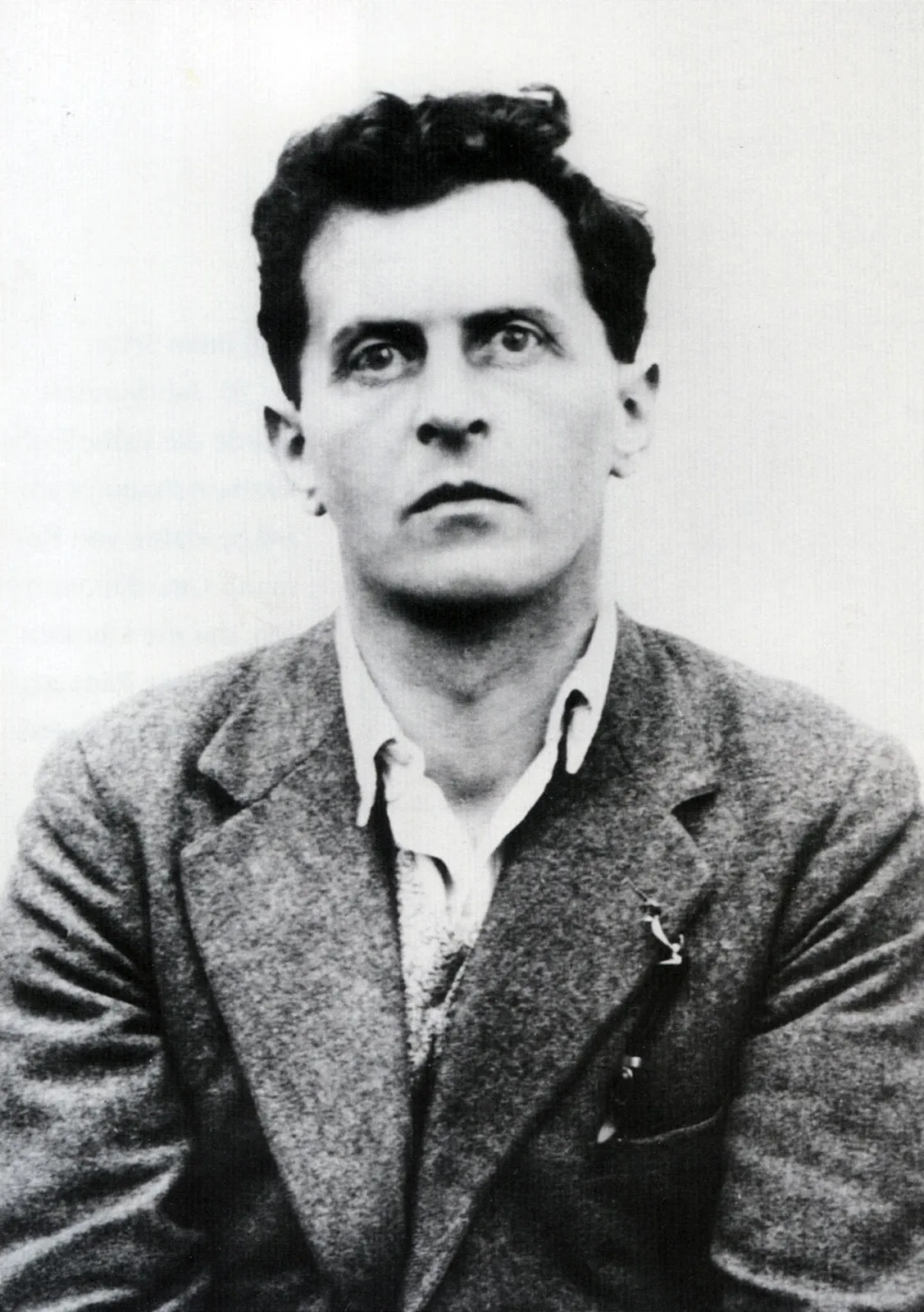

Sixty years, another world war, and a cold war later, Lyotard thought that the reaction against modernism resulted in “incredulity against metanarratives.” So let’s define a “metanarrative” as a type of grand, justificatory language game. A language game is a concept from Ludwig Wittgenstein that posits that language does not arise in the abstract or for purely formal purposes, but exists within a broader context of action and desire to communicate meaning. Therefore, every word or sentence uttered in a human tongue acquires meaning according to the “rules” of the “game” being played by that language.

Now, Wittgenstein is one of the foremost analytic philosophers and one of the most influential of his day or even today. In the post-WW2 era, Wittgenstein’s focus on language led to a “linguistic turn” in analytic philosophy where philosophy went from the analysis of pure concepts of the understanding to language itself. Wittgenstein’s observations about language are fundamental: language need not correspond to some objective reality and our concepts do not require Cartesian clarity to obtain meaning; all of this arises in conjunction with what we want the language to do.

Lyotard explicated this theory that “metanarratives,” those grand language games we had been telling ourselves about what it means to be human or rational beings or whatnot were slowly losing their power. Marxism, modernism, religion, the natural sciences, etc., whatever we were using to give our lives meaning and inject into existence some form of order, he argued, were slowly losing their ability to mystify us and hold our attention.

For example, in the case of the natural sciences, the natural sciences required a non-scientific “handmaiden” (analytic philosophy) to continue to justify their primacy in explaining the world. That is, scientific thought requires the notion of an objective truth that can be known by limited beings such as ourselves if we intend for the products and conclusions of science to have normative force.

But, as was shown by the last 100 years of thought, that picture is false. Scientific knowledge is all relative to a given scientific paradigm (e.g., in Kuhn) that can, within the span of a decade, be completely overturned as we amass new data. To scientists, this presents no problem; hypotheses are only hypotheses until disproven, and we can go on with new science as long as we comply with the meta-rules about science. But to the general public, who find themselves in the postmodern condition, it must seem as though science has no fixed star. Science is therefore unable to transcend its particular mode of discourse to claim that its language-game should have primacy over others, such as religious or philosophical language games.

The second problem Lyotard highlighted with the notion of metanarratives was their tendency to be teleological or have an “operativity criterion” toward knowledge. That is, we do not gain knowledge for its own sake, but in service to other motives, be they political, economic, sociological, or otherwise. Think of every scientific breakthrough you hear about: if the next question asked by the media is not “but how will this affect us? When can we expect to see this in production?” then that question will very soon follow. As long as we let scholarly research be dictated by donors and economic interests, Lyotard thinks, then we have lost the epistemic plot.

So, to wrap up this rather long and meandering thread, “postmodernism” is that group of theories and thinkers who, when faced with a crisis in human knowledge following the birth of the atomic age, saw folly in maintaining the old, modernist ways of thought that led us to the brink of nuclear Armageddon and wholesale destruction of the globe in the name of laissez-faire politics.

This, naturally, made some philosophers, mainly analytic ones, very sad, because they either had a socioeconomic or political state in the atomic age state of affairs, or had an attraction and attachment to a theory of rationality, truth, and knowledge that was incompatible with the emerging holistic and heuristic models proposed by these thinkers.

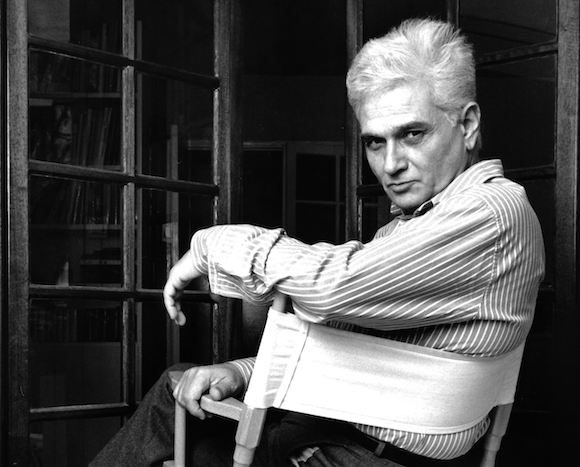

Thinkers like Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Jacques Derrida, Edmund Husserl, and the like all wrote about rejecting traditional philosophical models like identity, binaries, scientism, etc., in favor of more free and creative ones. In doing so, they directly challenged modernist ideals about rationality, truth, and objectivity. Thus far, Wokal is correct in quoting Searle.

But where Wokal goes wrong is when he says:

For this reason the postmodernists do not play by the intellectual rules that have been set out by what we might call the western tradition of rational thinking. The standards for reason, logic, argument, coherence, truth, and so on are being challenged, attacked, undercut, subverted, and called into question by postmodernism. This means that the clearly defined, well argued, intellectually coherent arguments that we typically want from academic work are not always present in postmodern philosophy, and in some cases there is an open hostility to demands for objectivity, logic, clarity, and coherence within postmodern writing.

This is a common misconception, that because the “postmodern” thinker critiques reason, logic, argument, coherence, or truth, that the thinker finds no value in it. Leaving aside whether modernist arguments are “clearly defined, well argued, [and] intellectually coherent” the standards by which those arguments were constructed were all a part of a Wittgensteinian language game meant to authenticate, privilege, and elevate those kinds of discourse above others. Being skeptical of the purity of motive and purpose in such things hardly calls into question rationality. After all, postmodernism is nothing more than modernism’s insistence on the centrality of rationality turned back upon itself.

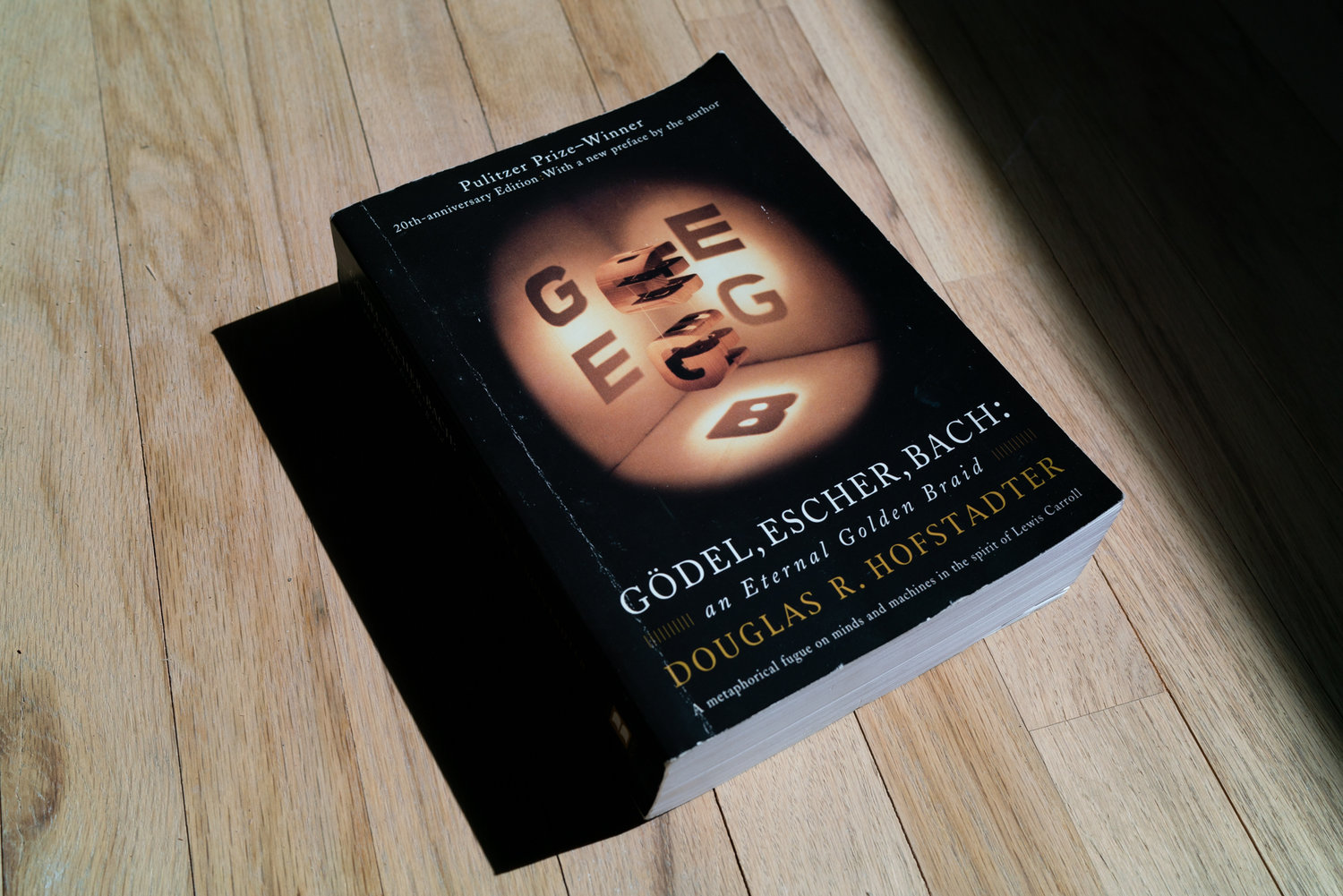

A strange thing happens when you examine recursion. Although not the best work of philosophy, Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid is nevertheless a good rumination on the problem of recursion and self-reference in formal systems. It turns out, trying to get a formal system to justify itself is really, really hard. You end up in strange loops because the foundational, stepwise assumption of post-Aristotelian rationality turns on everyone agreeing with Aristotle about certain ground rules for rationality.

The more conservative members of the Academy of course saw this as little more than footnotes, because disagree with the Great Aristotle? You must be mad! But why should we, possessed of inquiring and scientific minds, make an idol of Aristotle? What privileges him above question? And thus we devolve back to Nietzsche: where one finds that one has made an idol, one must take up his hammer. The more sacred the idol, the more necessary the hammer.

Wokal takes Nicholas Shackel as his Virgil through this purgatorio, arguing that we can lump into the category of “postmodernists” everyone who expresses the slightest skepticism about the modernist project, including, but not limited to:

not just self appellating postmodernists such as Lyotard and Rorty, but also post-structuralists, deconstructivists, exponents of the strong programme in the sociology of knowledge, and feminist anti-rationalists. I unite them under the term because, philosophically, they are united by a sceptical doctrine about rationality (which they mistake for a profound discovery): namely, that rationality cannot be an objective constraint on us, but is just whatever we make it, and what we make it depends on what we value

Wokal appropriately sums this up as:

the common thread of postmodernism is the belief that rationality cannot be an objective guide for us because we make up the rules for rationality, and the rules that we make up will be a product of our self-interests, biases, and culturally constructed values.

Not to be too flippant about it, but if that is the conclusion of “postmodernists,” then I would like to see some argument against the essential correctness of that conclusion. Wokal may of course object that any attempt to show the bankruptcy of such a view would of necessity require the use of rational argumentation, standards of evidence, etc. and so on, but the point is: rationality cannot survive under its own rules. It is a strange loop!

The reason why this is bad is put forward in the next paragraph:

According to Shackel this leads to absolute irrationalism.

Suppose this is true.

There is a hidden premise in Wokal’s argument, that “absolute irrationalism” is bad. The question we should be asking Wokal is: if absolute irrationalism is bad, why is it bad? If the answer is, “I can’t use objectivity and rationality as a club against people to get them to behave like I think is proper!” then I ask whether rationalism is any better than a pharaoh-paid overseer cracking a whip.

Wokal argues:

Once you get rid of objective standards of rationality attempts to find anything like objective truth or objective morality are going to end up failing, for without an objective standard of rationality we will have no way to judge between competing ideas of truth or morality, and no way to build an objective standard of truth or morality. This leaves us with utter relativism.

This kind of defeatist nonsense is common. If one abandons the idea that there is a (human-knowable) objective truth, what we are left with is good old-fashioned Kantianism, that truth is mediated by human cognition. That does not mean there might not be universal truths, or truths so well-established they are beyond question (2+2=4 in base-10 seems rather safe), or that we might not have some other criterion for judging between two competing ideas, just that we cannot do so with Kantian “pure” reason; we might have to resort to practical reason or (gasp!) the use of judgment.

One of the more common sophomoric objections is that under an “utter relativism” we cannot say that a group of man-eating cannibals is objectively worse than a tribe which eats only the freshest fruits and vegetables, that we must assume a kind of moral equivalence between Eloi and Morlock.

But this not true; what it means is that the old language game of “eating human flesh is wrong because my God said so” or “eating human flesh is wrong because we have scientifically studied it and it turns out it increases net unhappiness” or “eating human flesh is wrong because it treats others as a means rather than an end” are not cudgels by which we can coerce changes in behavior.

Remember that the idea that morality was objective and known/possessed by particular peoples led to the ills of colonialism, the “white man’s burden,” and imperial conquest. Life becomes easier to do what you want without caring about its effects on others if a man believes his god (including the god of reason) licenses and sanctions his conduct.

But nothing about any of these thinkers should lead one to believe that they could not find a moral or intellectual objection to Morlockism; merely that any such attempts must be couched in the language for what they are: we don’t like the Morlocks because they sin against God, but because we would very much like not to be eaten. That does not de-legitimize our desire not to be eaten, but it does contextualize it.

But in Wokal’s world, pace Searle, he believes that:

the traditional university claims to cherish knowledge for its own sake and for its practical applications, and it attempts to be apolitical or at least politically neutral.

The question for Wokal and Searle is whether the “traditional university” ever had or attempted to live up to that ideal. If the answer is made: “that never happened,” then it must be incumbent upon Wokal and Searle to show that this mythical apolitical golden age of knowledge-for-its-own-sake existed. But a casual perusal of history will show that it never did, going back to the Platonian Academy in Athens.

If indeed it is true that the “postmodernists” seek to use the academy to achieve political goals, then at least they are honest about it. Just like an anti-formalist in the law may acknowledge when she is engaging in motivated reasoning to reach a result in a case she thinks is correct, plain or original meaning be damned, at least she has the fortitude to recognize when she is engaging in motivated reasoning and own up to the fact, rather than couching it in some terms of high-minded theory that “compel” a particular result that just so happens to be right in line with what the judge wants.

Another claim Wokal advances is that reading “postmodern” thinkers is hard, because they mainly wrote in languages other than English, and translations may not be the best. Further, he argues, the diversity of thought among this ad hoc grouping is so great that one cannot impose any “logical order” on them, and instead that “promoting these very different thinkers somehow contributes to a shared emancipatory political end, which remains conveniently ill-defined.”3

While it is certainly true that many of the critical theorists, particularly of the Frankfurt School, were explicit in the liberatory and emancipatory goals of their philosophy, that is less true for many of the other thinkers listed. Although many of them were at least somewhat sympathetic to progressive causes, so were/are most academicians. Educational achievement is loosely correlated to progressive politics for a reason; smart people tend to have fewer idols, and those idols they do have tend to be couched in a deeper understanding of the world.

From this, Wokal draws:

What we see here is the idea that the guiding light of the postmodern thinker is not truth, it is a commitment to a political agenda.

and this is again wrong. The political agenda is not the guide or lodestar for postmodern thought; it is a realization of the fact that the political agenda is ever-present in all forms of reasoning. The postmodernist is merely honest with herself in a way the objectivist is not. The objectivist denies his work is “political” in a way the postmodernist finds disingenuous, or at least ignorant.

When Wokal writes:

Thus, the key question to the postmodernist is this “who benefits from accepting these standards, ideas, concepts, categories, and claims?”

the suggestion is that this question is not “key” to the objectivist or should not be asked at all, which seems rather foolish. The only reason not to ask this question is that one would be afraid of the answer, afraid the answer might reveal a previously-unconscious or hidden bias in thought.

Despite his ignorance of his own hidden premises, Wokal continues:

In other words, the postmodernist is concerned about politics and power rather than truth.

The hidden premise here is that one ought to be more concerned with truth than politics or power, but there seems to be little support for such a premise. After all, if research funding at a major university is tied to the whims of donors or the ability to make money off of patents obtained by graduate students, then politics and power drive the quest for knowledge and “truth.” Truth becomes a fungible commodity in the information economy.

Wokal concludes:

The simple way to put this is that the traditional western conception of academia was concerned with what is true. Whereas the postmodern conception of academia is concerned with POWER, who gets is, who wields it, and who benefits.

This is simple, and wrong. The traditional western conception of academia thought it was concerned with what is true, but very often “truth” became “what the academy wanted to be true for temporal and political reasons. The postmodern conception is not to be concerned with power for its own sake, but in recognizing the way power structures, who had it, who wielded it, and for whose benefit, shaped the goals of the academy and attempt to correct for such structures.

Wokal leaves us with the idea that “[p]ostmodernism cynically adopts theories which allow it to tear apart well validated and rigorous ideas that are essential to our societies view of the world in order to advance a radical left wing political cause.”

Crucially, he does not specify which “well validated and rigorous ideas” are so under threat, nor how ideas of such unimpeachable pedigree could ever be truly threatened by the tools of rationality, so cynically adopted by nefarious thinkers. It is the same old boring whine as always: “when you turned the tools of rationality against my sacred idols, they crumbled just as surely as the idols I sought to destroy.” And for anyone bereft of the ability to philosophize with a hammer, that seems a bad situation.

But for those who recognize that the process of knowledge, the growth of society, and the evolution of the human race is more organic and less dependent on “well validated and rigorous ideas” than it is on creativity, freedom, art, and independent thought, turning the tools of rationality against themselves seems not only appropriate but essential.

When Wokal thinks he is exposing the nefarious plot of “cynically creating theories in order to help them grab power, advance their ideological causes, and implement their political views,” he presumes that doing the opposite of that somehow isn’t “cynically creating a theory in order to help [him and others like him] retain power, advance their ideological causes, and maintain their political views.” That is, it is of course legitimate and meet that Wokal and those like him should continue to hold temporal power, advance their ideological views, and shut out the “left wing radicals” who wish to remake the extant and perfect modernist society into something new.

He exhorts us:

The sooner people realize that postmodern ideas are not the fruit of rigorous, careful, enlightenment liberal scholarship, the sooner postmodern ideas can be subjected to the scrutiny they deserve.

To which I reply: the “postmodernist” would welcome the scrutiny. But while they have built into their philosophy the allowance and tolerance for error, the notion that two contradictory things may be true at the same time, and that there is room among equals for creativity, passion, and experimentation, it is the rigid dogmatist of modernity who feels that there is a “clash.” In such a situation, modernity is locked into a struggle with its own mortality, while post-modernity asks it to sit down and have an honest conversation.

As much as Wokal and his confederates (of which there are many) would like you to believe that they are the last bastion of defenders of the faith against encroaching barbarian hordes, I ask that you consider them instead merely stodgy old stumps stuck in the mud of yesterday’s philosophy, refusing to move or acknowledge because they are comfortable where they are at, and are no more above “putting their fingers on the scale in the name of advancing their political goals” than those they deride.

But if one is honest about ones intention, does not seek to hide it, and otherwise states outright that “this is my goal and I will pursue it,” then who really should you trust? The one who thinks themselves somehow above the human condition, or the one who admits it and embraces the insecurity that implies?

The point of my post, moreso than simply responding to Wokal (and those like him) is not to convince you to be a “postmodernist.” I am not sure that is a thing. But I do hope that perhaps you will not reflexively shun these ideas as “irrationalist” or “relativist” simply because they contain a critique of the notion of objectivity or some sort of transcendent, human-knowable value. I hope you will simply keep an open mind and engage critically with the ideas of thinkers like Deleuze and Guattari or Derrida, rather than dismissing them out-of-hand as the Anglophone academy has since the 1950s.