Capitalism & Schizophrenia Part II: Flow and Territory

How our activity and history combine to create particular features of society.

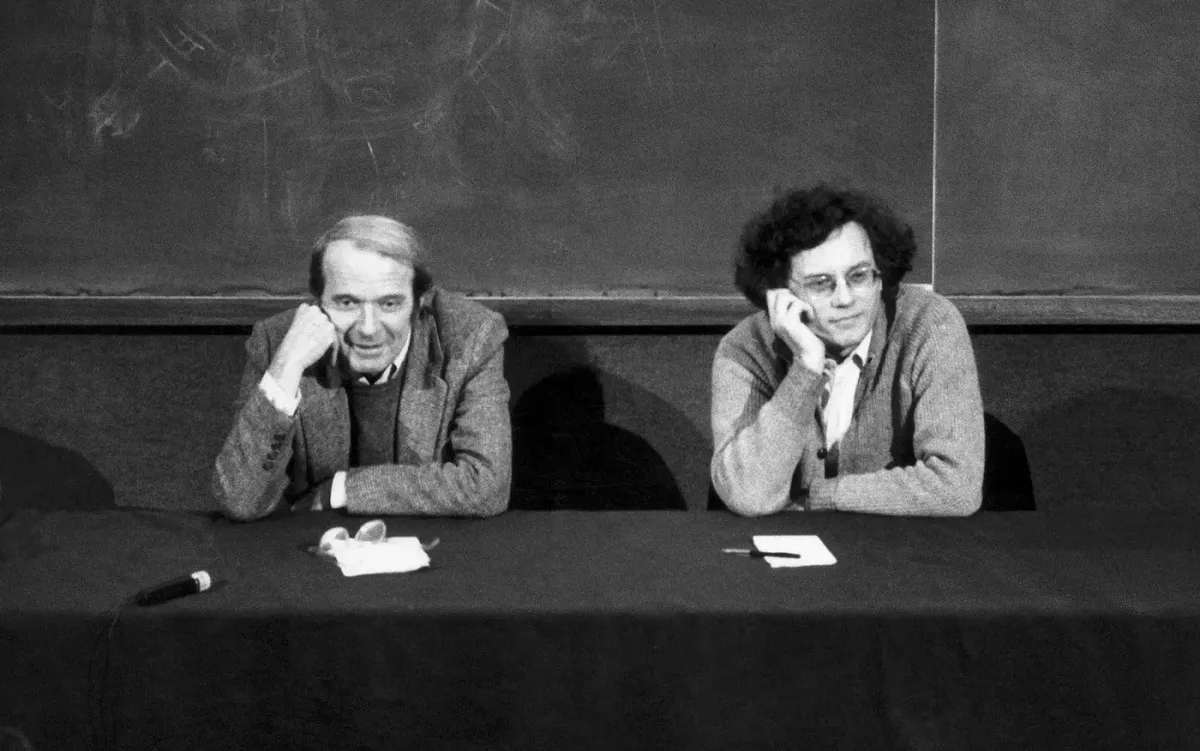

Author’s note: welcome to part II of… some number… of posts explaining the seminal work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Capitalism & Schizophrenia, or at least its first part, Anti-Oedipus (the second part, A Thousand Plateaus, is really more of an exemplar than a theoretical work, though I’m sure I will discuss it at some length, perhaps not with the same focus as Anti-Oedipus). The purpose of these discussions, as will become clear, is hopefully the offering of an alternative leftist politics and mode of organization that I believe is more relevant and more pragmatic in our fallen age.

As we saw last time, Deleuze is a philosopher of difference, who seeks to upend traditional notions of metaphysics and ontology by adopting something very much like what the analytics would call “process metaphysics,” though Deleuze goes further and redefines every element of his ontology as a “machine,” something made to accomplish a purpose. Everything is machines, or complexes of machines, and the relation between machines relates to desire, which is for Guattari not the psychoanalytic/Freudian notion of a lack in the subject but rather a real and motive force that shapes and powers the machines. Desire is not merely the recognition of a lack in the subject (because there are no subjects, merely more machines) but what causes one machine to reach out and combine with another to reach a new objective, subsuming and making that objective part of the machine itself.

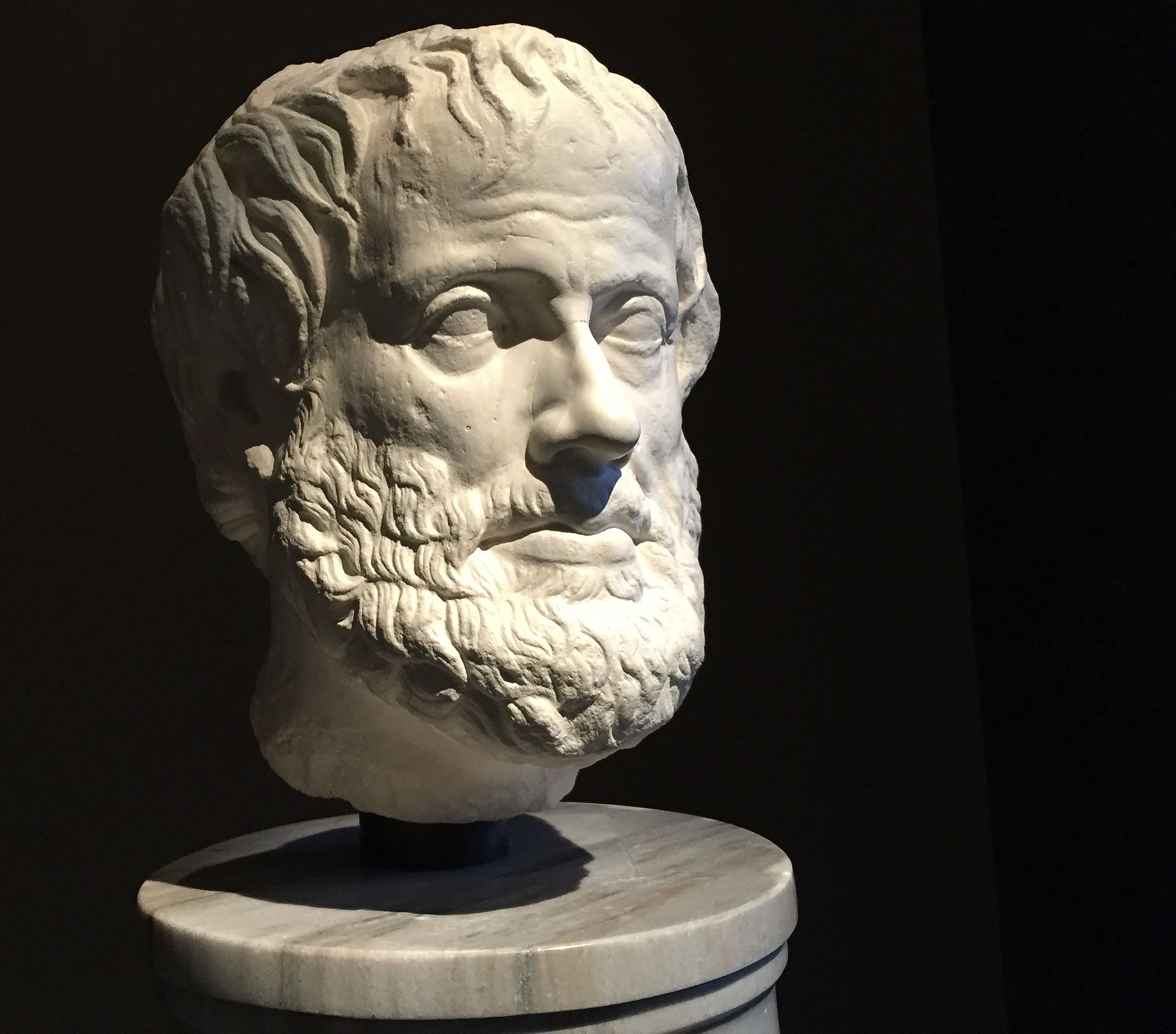

With this as background, we need another metaphysical category to describe the activity of machines in concert, or what D&G call hylë or flows. Hylë is a concept from Aristotelian philosophy; Aristotle argued that every entity or being was a compound of matter and form. The word “hyle” is Greek for wood, which more or less meant “matter” or “material essence” to Aristotle. Form, of course, being something akin to Plato’s forms, but for Aristotle, were not transcendent categories of Being but rather immanently real things within individual beings. Aristotle said that his hyle was comprised of the four classical elements, but it works equally well as a modern theory concerned with quantum particles. Hyle is stuff.

But for Deleuze and Guattari, who have already resisted defining things in terms of static identities, machines have to be made of something, and so they get the generic term hylë, which is represented in “flows.” Now, like a machine, a flow is anything and everything so long as it involves a movement from one point to another. D&G are careful here to say that flows encompass everything from capitalism (the flow of labor and capital) to population trends (the flow from rural farms to cities in the Industrial Revolution, etc.) to the shit flowing in the Paris sewers (the vulgarity is deliberately chosen by D&G to show the ubiquity of flows). Flows define activity in an eco-social metaphysics. If everything is machines, flows are how we describe how those machines interact, interrupt, and break each other. In fact, D&G say that you really only learn what a machine does when it breaks, that is, when it does not accomplish what it is meant to, because that is when the flow gets interrupted and you start to see the effects of what it did all along.

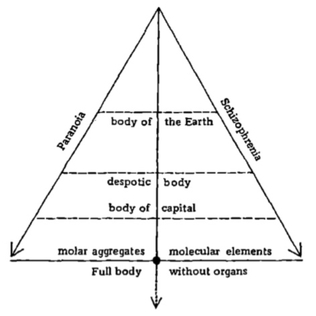

So it is inevitable, they think, that machines should break, and flows should be interrupted, and that this pattern gives rise to the structure of society. In doing so, they describe several quasi-anthropological “stages” of the “body,” here not concerned solely with actual bodies but rather then concept of a “body” or complex of machines. Remember, this isn’t supposed to be a book of philosophical anthropology. This is a metaphor for understanding in the schizophrenic sense rather than something you are to take as literally true. We begin with “tribal” or basic societies, who trace their body back to the Earth itself (or some mystical region of Earth, like the Garden of Eden), that then become the barbarian or imperial body where they are owned by the sovereign, and finally find their present historical circumstance as commodified in capitalism. This type of flow is thus “territorialized,” that is, traced to the earth as the source of production. It carries with it certain signs and signifieds, the linguistic/semantic concepts employed to make communication in these socieites/territories possible, or in other words, to permit relations between machines and flows.

The flow becomes “deterritorialized” in the imperial stage, as the sovereign them becomes the source of production, effectively reterritorializing them in the body of the sovereign, who assumes credit for the productive value of the flow. When this happens, the previous signs of the tribe are overwritten, forming what they call the “deterritorialized sign” that allows for communication between the body peasant and the body sovereign, or a flattening/bi-univocalization of the signified.1

Capitalism is a similar radical decoding/encoding of territorialization of material flows that the previous social machines had coded on the body imperial. Capitalism is a machine that functions as such: connect the deterritorialized flows of capital and labor to extract a surplus from the flow. Capitalism is enormously productive as a flow, almost as a rule, because it uses desire for greater accumulation of capital to power many different flows, for those flows to be made more efficient (at pressuring the flow of capital from labor to capital holders), etc.

Now that we’ve dealt with flows and territory in action, let’s go back and break down these concepts and investigate them. If it sometimes seems like my method of explanation here is circular, it is. And that is the point. Deleuze and Guattari are using these concepts both as literal terms (territory and bodies mean exactly that, land and people) and as metaphors (territory becomes the intellectual abstract of Cartesian space in which our intellectual problems are represented) and bodies are complexes of ontological machines. This is a feature, not a bug, of Deleuzian philosophy. You never throw away the old way of doing things; you just create a special case where it is necessary within your greater, broader view. The same way that Newtonian mechanics were not abandoned when we discovered general and special relativity. They just became unique cases where those rules applied.

In this way, we do not entirely jettison the philosophies of static identity, Being, bi-vocity, etc., we simply limit them to cases where they are useful for helping us grasp the multiplicity of shifting identities present in flows.

In that way, territory is both a plain meaning (literal physical space) and an abstraction of intellectual space into which we can represent and present conceptual objects like “capital.” In this way, Deleuze is pulling us to think about the nature versus nurture debate, something very much at the heart of psychoanalysis, with its conceptions about the pre-conscious mind, and Marxist theory, with its concerns for superstructure imparting to us certain values. It also ropes in structuralism and post-structuralism from the previous post about, say, Barthes, and the idea that we are not pure Kantian sui generis subjects freely choosing attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, etc., as some sort of super-rational moral agent, but firmly located within our historico-cultural context.

Put another way: we know that all societies develop language games to create conceptual spaces in which can represent our intellectual and social problems to attempt to solve them, since only with reference to those language games can we ever hope to evaluate statements to address those problems. The language we use in those games is an encoding, and the space in which we represent them a territory. The process of creating these sign/signified relations and demarcating the territory are important for the evaluation, but we must not neglect the nature of their relation to our world of machines engaging in desiring-production through the use of flows. That is, an encoding and a territory are a temporary imposition of order on the mass of chaos that is desiring-production/flows, for the specific purpose of attending to something that is causing a breakdown in the flow-structure. And what do we call a thing made for a purpose? A machine. EVERYTHING IS MACHINES. So if that’s a machine, then are we about to encounter a way in which that breaks, and an interruption of the historico-ideological flow we call “human history?” You bet!

Like all of Deleuze and Guattari’s points, however, they do not wish to settle the nature-versus-nurture question; rather, they want you to see that the question itself arises from the old, bad way of doing philosophy. There isn’t a clear distinction, in their minds, between what is nature and what is nurture, because who nurtures you also is subject to nature, and “nature” itself is a product of thousands of years of different kinds of nurture. Think back to the triangle: there was never a magic moment in time when we as a species became divorced from our tribal past; that past was never “done away with” and we never emerged as civilized modern Frenchmen out of whole cloth. Rather, our previous tribal identities, whether as Franks or Normans or Iron Age Celts or Bronze Age farmers or Stone Age hunter-gatherers were overwritten, re-territorialized, given new signs and language as Romans or Germanic tribes or Goths or whoever conquered us, and thus we began new flows, we developed new desires, and built new machines to respond to those desires and participate in those flows. You could no more answer the question of whether you possess a “human nature” or “French nature” or “Germanic nature” than you could answer whether your nurturers did or their nurturers or whatever. You, and your conception of identity, are a flow. You are machines upon machines engaging in desiring-production with blood and shit and ideas and concepts and everything else in flow as you participate in, change, and are changed by, modern society.

To think that you possess some sort of stable identity in all of this would be… madness! You might even say that to adopt the idea that you possess some sort of stable identity through all of this would be akin to the way a schizophrenic describes the world. This is why the two sides of the triangle that form the apex are labeled “paranoia” and “schizophrenia.” Paranoia is the desire to code, to territorialize, and reterritorialize every breakdown in the machines and flows as they happen.

It is the force that says “order this chaos.”

Schizophrenia is the opposite; it is the destructive nature, the chaotic, the one that resists the falsity of the imposition of order.

This traces back to what Freud (and presumably Lacan) were after in describing the Oedipal relation as primary, and gives us our first insight into the name of the text: against Oedipus.

For psychoanalysts, the Oedipal relation arises during a stage in childhood development where we learn to be moral and suppress the basic possessory and territorial urges. Freud saw this as obsessively coded in modern society, with notions of rank, class, race, etc., as a part of this Oedipal relation. Deleuze and Guattari think that this is wrong and wish to argue against it; they see the Oedipal family as one of repressive social relations, relegating everything to dominance and power relations out of a fear of the psychoanalytic concept of castration.

This, to them, does not account for the presence of desire in social relations. This is the old, bad concept of desire as a lack rather than a vital force. And it is the reason, they think, that old-order politics like Marxism have failed, because it still uses the language of hierarchy, domination, and lacking/desire rather than desiring-production.

So our twin drives to obsessively encode/territorialize and our other drive to decode/deterritorialize are what drives us through this process of decoding/encoding or deterritorializing/reterritorializing. In this way, Deleuze and Guattari hope that they have provided a model that subsumes both Hegelianism and Marxism in their accounts of material/ideological history as well as our broad-sketch philosophical anthropology.

At this point in the text, we should feel like we have grasped their re-definitions of humanity as complexes of machines engaging in flows, watching as those machines break down and flows get interrupted, and in these interstitial spaces code and territorialize language and concepts to explain that, but with that process ever ongoing as our understanding of both the semantic meaning and conceptual space in which we represent those concepts as growing as the flows move on. In doing so, we should see an epiphenomenon arise where we can, at times, snatch bits and pieces of meaning and identity from the ongoing work.

In the next chapter, we are going to look at rhizomes and the body without organs, and hopefully impart some paranoiac structure on the schizophrenic chaos while at the same time allowing the chaos the freedom to grow, change, and be changed.

Think back to our discussion in part one about semiotics and the signs/signifieds. This is a part of how communication across territorializations is possible. ↩