Capitalism & Schizophrenia Part III: Rhizomes and Bodies

To liberate your mind from the structure imposed by capitalist reterritorialization of your conceptual schema, you must first drive yourself mad.

As we saw in our last outing, Deleuze and Guattari offer us both a new epistemological and metaphysical basis for understand the world around us by breaking down identity and objects and relations into machines and flows, powered by a reevaluation of the psychoanalytic concept of desire (instead of a lack, a positive force) and the Marxist concept of production. So what happens if we adopt this view, abandon the metaphysics of identity in favor of looking at the world in a more dynamic fashion?

The answer, according to Deleuze and Guattari, is that we need new models of organization. A typical model that we might use is that of a tree: trees have their base in their roots, structured throughout the trunk, and then branch off into individual branches and leaves. This traditional model of structure is not without some value, they say, but it cannot encapsulate everything we want in philosophy.

In particular, the problem with the tree model is that it is too rigid: it has definite stopping and starting points (roots, branches) and a definite flow of ideas and information, from the roots, through the trunk, and out to the branches. When you see a tree diagram, you instinctively know how to orient it. This type of structure is imposed.

And this brings us back to talking about the structuralists/post-structuralists. Remember that in the decades preceding the writing of Anti-Oedipus, French philosophy was very concerned with structuralism and the response to it. For a refresher, “structuralism” is an approach in philosophy and the social sciences, especially linguistics, that arose in opposition to existentialism. Whereas existentialism posited a sui generis subject who was radically free to choose from among value systems and conceptual schema, structuralism argued that a pre-existing structure (see the Marxist concept of “superstructure) actually informed those choices. Together with semiotic philosophy around language and representation, thinkers like Claude Lévi-Strauss and Ferdinand de Saussere developed an analysis of language and representation in terms of signs and signifieds giving rise to particular semantic/doxastic “structures.”

Later thinkers, including the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, would apply structuralist principles to psychoanalysis, leading to the idea of “constructivism,” or the notion that the sciences, including social sciences, are not dictated by a relevant objective model or objective principles but rather constructed models chosen for their fit to a particular paradigm. Thomas Kuhn would later describe the changes of these paradigms in terms of selecting new structures under which to practice scientific methodology.

So if the tree-structure that we have been dealing with has been a part of the dominant paradigm for the entire history of Western philosophy, Deleuze and Guattari aren’t recommending that we throw it out altogether. Rather, they want us to understand that it is a limited case, but a particularly useful one, because that structure (modernism) has been very influential in developing our understanding of the world around us and giving birth to the natural and social sciences.

But that structure is also bound up with everything else in our society, including the capitalist mode of production, which again is at the outset something Deleuze and Guattari wanted to supersede, in a non-Marxist fashion. Or at least, in a heavily-modified Marxist fashion by changing the relevant conceptual superstructure.

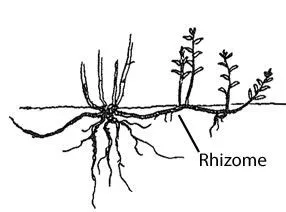

To do that, they argue that we should adopt a “rhizomatic” perspective. Think of a wall of ivy. Ivy as a plant is rhizomatic; it has no constituent parts that are identifiable as a “head” or a “body” or a “foot.” It is all vines. You can look at a wall of ivy and never be able to pick out which vine is oldest, or primary, or central. Each node of the ivy vine is much like any other.

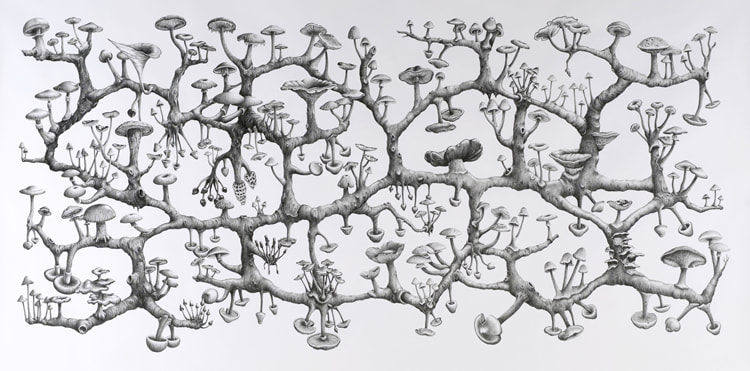

And it can grow or combine in any way it needs to in order to give itself structure. It will grow to carpet the ground, or climb a wall, or encircle a tree trunk. It’s a rhizome. Formally, Deleuze defines a rhizome as a network that can connect from any point to any other point, with no fixed order. By organizing things in terms of a rhizome, rather than a tree, you free the concept under evaluation from the strangling structure and enable the concept of multiplicity.

The concept of multiplicity is important because, as we abandon the philosophy of identity to embrace a world of machines and flows, things are not just one thing any more, or a unity of different things in one. They are a compound thing; they contain multitudes; they are multitudes. But this way, you can talk about multiplicities as if they have a moment of stable identity, the same way a physicist can arrest the motion of an electron to determine its position, a collapse of the conceptual wave function, if you will. However, like the physicist, you are also aware of the artificiality of the position of the electron; you just need it for your model. The same way Deleuze and Guattari think that a rhizomatic, constructive model for concepts will enable new forms of analysis and free our thought from the rigidity imposed upon it by “arborescent” structures.

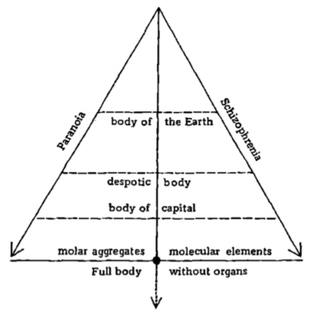

That is because rhizomes are “not amenable to any structural or generative model.” They represent the schizophrenic pressure in our diagram, the resistance to structure, the need for free and creative expression outside the boundaries of what we know.

In this way, we reach the bottom of the schizoanalysis diagram: the full body without organs. The Body without Organs, or BwO, is one of the most difficult, nebulous, and ill-defined concepts in Capitalism & Schizophrenia. In fact, I would go so far as to say that it is easier for a child to understand the concept than a learned scholar, because the very concept requires that you throw away so much of what you know or have learned in your education.

It comes from a 1947 play, “To Have Done with the Judgment of God,” by Antonin Artaud. Referring to man as the philosophical subject, in the epilogue, the author states that, “When you will have made him a body without organs, then you will have delivered him from all his automatic relations and restored him to his true freedom.”

This is again a callback to the tension between existentialism and structuralism, the question of are we free, or are we merely ignorant of whence come our desires and fantasies? And again, we are back to the psychoanalytic concept of the unconscious, the blank darkness that arises before our thoughts and actions.

So what are “organs?” Obviously, Deleuze and Guattari are referring to both literal organs, like your kidneys, or your intestines, as well as figurative organs, like the organs of state power such as police or a legislature. Organs are linguistically tied to organization, but also to organisms and organic growth (see also: arborescence and rhizomatic growth). All of this is to say that organs are things which give structure. Organs are very much like machines; they do a thing, but their shape, their purpose, their place within the network, that gives a definite structure to things, a direction to flow, a purpose. That kind of imposition is arborescent, not rhizomatic. The rhizomatic body is a body free or organs, or in Artaud’s poetic license, someone who is free from the superstructure-imposed values, concepts, ideas, and so forth. It is a way of escaping the structuralist problem and becoming the free and creative existential subject.

It is our path away from politics and philosophy as usual, our way of becoming new. And all it takes is a recognition that everything in your world, from your values, to your language, to your very thoughts, are not things you necessarily chose yourself, but were imposed upon you by thousands of years of culture, upbringing, evolution, psychology, and so forth. It is your attempt to wrest control of all circumstance away from the world around you and ground yourself solely within your own reason, your own perception, your own understanding: by making yourself a singular madman, refusing all structure that is given to you, you can choose a constructive model that best suits your needs at a given time, adopt that structure provisionally, for a purpose that you need, and then discard it when no longer useful. You have become a Body without Organs. The BwO is therefore limitless, pure potentiality.

Deleuze and Guattari go so far as to say that those who reject structure typify the BwO, but that should not be a goal we merely seek to replicate. Schizoanalysis is not simply adopting schizophrenia as our organizing principle; no, quite the opposite. The schizophrenic suffers; the negative experiences of freedom are what allows re-territorialization, re-coding, to allow structure to arise outside of conscious control.

They speak of “empty” bodies without organs as being pure chaos, totally undifferentiated, and “cancerous” bodies without organs as too stratified, too subject to what they call the “majoritarian” impulse that ultimately limits freedom again.

Instead, they seek something in the middle, the “full” but not cancerous body without organs, one that is de-stratified and de-territorialized, so that it may enter into new relationships/network nodes among the rhizome, but also “intensified,” that is, understood and invested with meaning so that those relations have a purpose and fit within a flow.

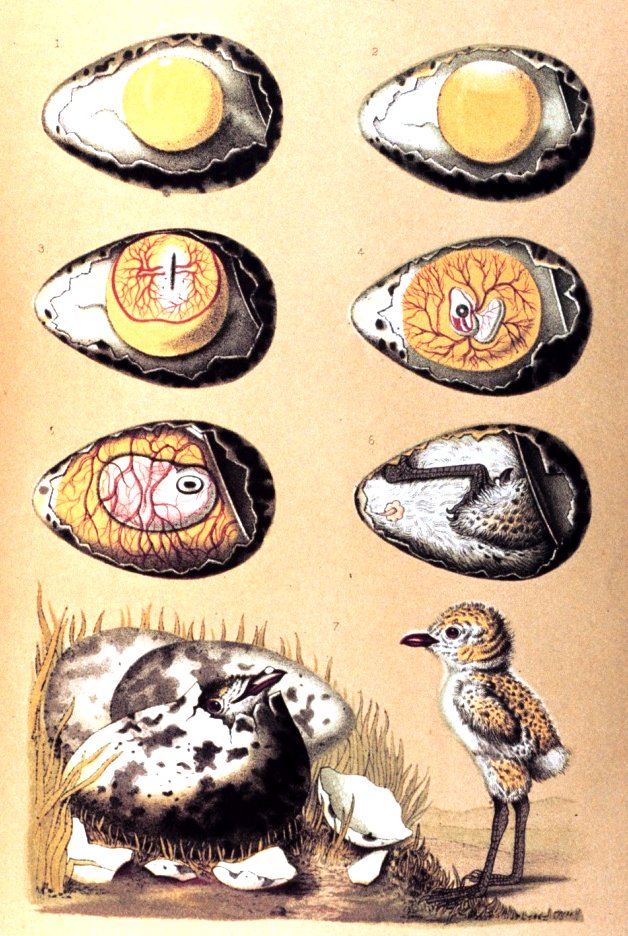

They analogize this to an egg; as a bird egg develops, technically nothing happens but the dispersion of proteins, which vary in intensity until the structure of an infant bird develops. There is life, a pattern, a desire, a flow, before the formation of the strata (the organs of the baby bird). It changes shape as necessary as it develops without being compartmentalized into specific organs yet.

This is the type of structure for conceptual analysis/social science/philosophy/psychology Deleuze and Guattari want us to adopt. They wish to see us become full bodies without organs, to regain our freedom from structure, but to be able to choose when to impose (and dis-impose) that structure at will as our needs and purposes change.

I promised at the conclusion of this series that I would hopefully show an alternative, leftist politics arising from these concepts. Now that I think we have some basic facility with the concepts at issue, I would like to propose that we conclude this lecture series next time in Part IV, with an adoption of schizoanalysis as a method and means from escaping continually-iterated political struggles.