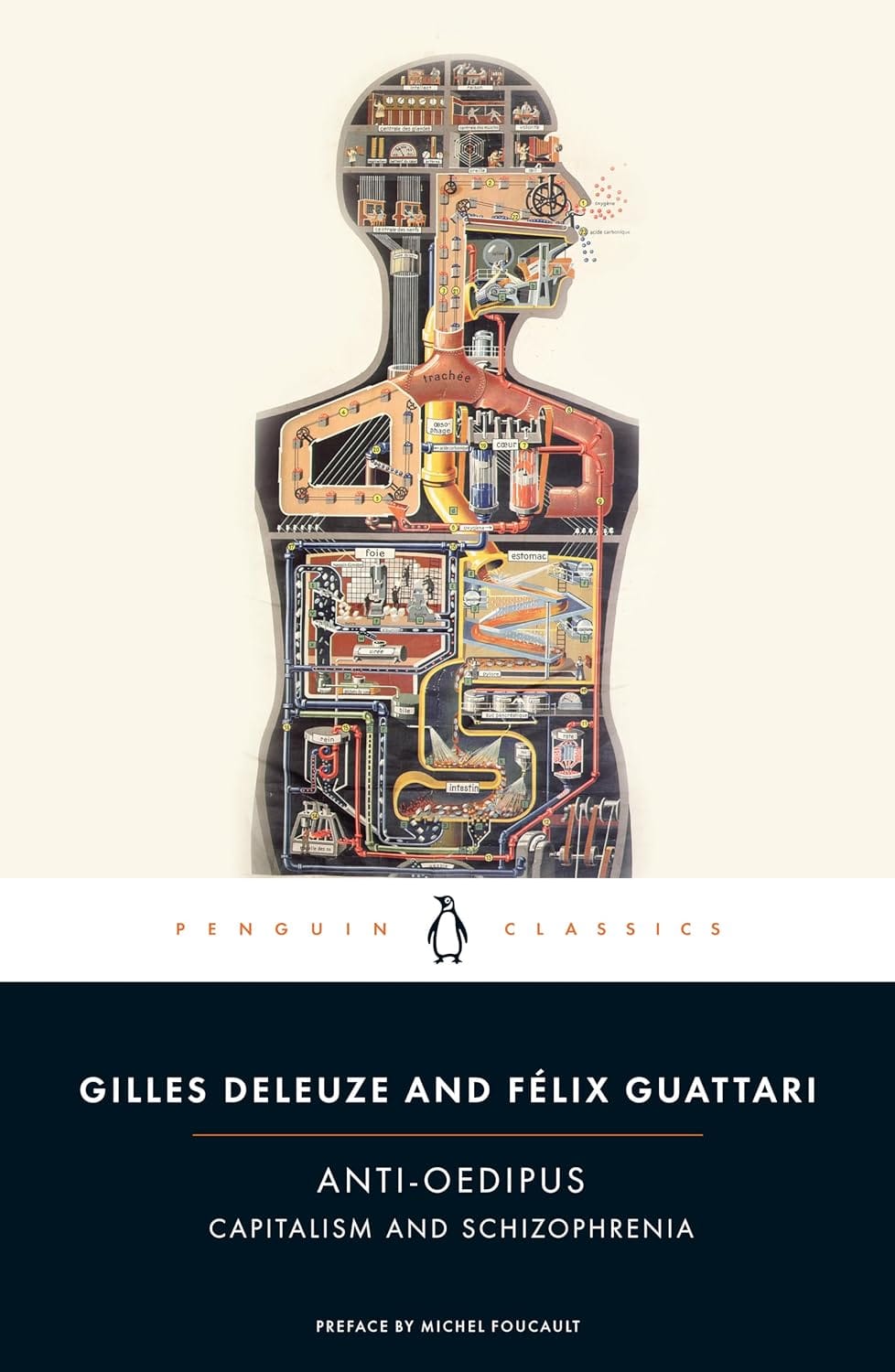

Capitalism & Schizophrenia, Part I: Devices and Desires

An explainer regarding Deleuze and Guattari's magnum opus and why it is politically relevant in 2025.

So I have been promising for some time to break down (at least the first volume of) Deleuze and Guattari’s principal text, Capitalism & Schizophrenia, entitled Anti-Oedipus. The reasons for this are twofold, mainly. The first is it lets me talk at length about something I am excited by, in the hopes that you might find it educational, and the second is that D&G offer up what I think is an alternative leftist politics that escapes the trap of ideology, particularly Marxist ideology, and a hope for a new kind of resistance in these latter days of fascist resurgence. The first taste is free; subsequent posts will (at least initially) be behind a paywall.

So, background. Gilles Deleuze was a French philosopher primarily interested in metaphysics and epistemology early on in his career, and later on with responding to and extending the philosophy of mass media we see in the structuralists and post-structuralists. Felix Guattari, his writing partner, was a psychoanalyst and treating mental health professional who felt that, by uniting his clinical practice with Deleuze’s radically new philosophy, they could respond to the post-1968 crisis in leftist politics and society by providing a new way of thinking about the world.

Obviously this type of discussion presumes some degree of familiarity with the underlying philosophical concepts, but I will try to do short digressions where necessary to provide the context and how to locate D&G within the history of philosophy.

So let me set the stage: it is post-war France. Fascism has risen and collapsed, and the great Marxist promise of the Soviet Union has backslid into totalitarianism and repression. In the West, the left-leaning Academy is left reeling as they attempt to revive the pre-war strains of thought that were rudely and harshly interrupted by the Second World War, while at the same time coming to grips with the post-war technological boom that gave us the mass media society.

In the Anglophone world, much of this work was done by people in the confusingly-named Frankfurt School, writing in English and American journals and attempting to reframe Marxism through the lens of cultural theory, sociology, philosophical anthropology, and so forth. But in France, we had a different approach going on, following the earlier strain of philosophical thought from the turn of the century called “structuralism” and its latter expression of “post-structuralism.”

Structuralism started when primarily linguistic-oriented philosophers like semioticians Ferdinand de Saussure and Roland Barthes encountered sociological philosophers like Claude Levi-Strauss. In particular, the semioticians were concerned with the emerging science of signs (semiotics). A sign, in semiotic parlance, is anything that stands for something else, like a word, or an image, or a logo, etc. The sign consists of at least two parts, the signifier (the word, logo, image, etc.) and the signified (the concept the sign stands for). Except that Barthes, for example, believed that one signifier could have many signifieds, not all of them necessarily intended by the signifier.

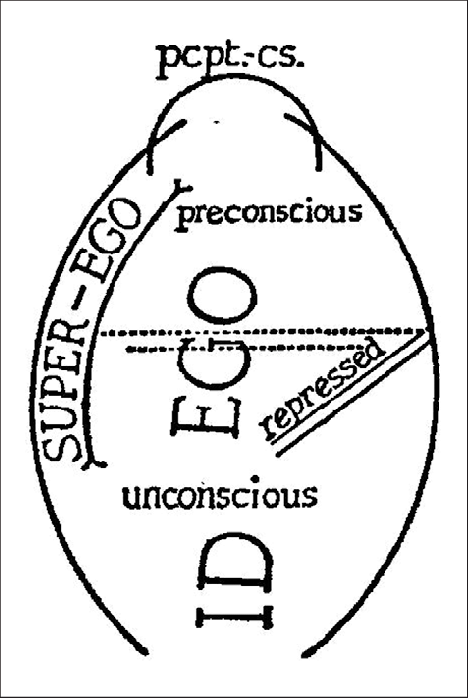

In doing so, Barthes was drawing on advances in the nascent science of psychology, particularly the psychoanalytic levels of consciousness we saw in Freud and Lacan. Believe it or not, before Freud, we can no idea of the unconscious or its role in our thoughts. The Cartesian subject was believed to be tabula rasa and to freely choose and accept from sensory inputs and cognition things like values, beliefs, actions, and so forth. But after Kant showed that the human subject cannot be tabula rasa, that the very least we require cognition to be intelligible to us according to our physical and mental faculties, that idea was out the window early on in the 19th century.

At the end of that century, Freud would explain that humans are largely ignorant of where these things like values and wants and desires come from, that they reside in our pre-conscious and unconscious selves. In particular, Freud would describe these in terms of drives and stages of development, each that contained a primary conflict/opposition that the self had to overcome to sublimate those drives and desires as a part of normal psychological development.

At the same time, philosophers were drawing on the materialist conception of history advanced by Marx, that the thing that determined the course of history was not freely-chosen sui generis subjects but the material economic conditions of that society. Like Freud, this took “responsibility” for things away from the individual and ascribed them to wider society.

Barthes, in particular, understood that a lot of this came from the “mythologies” that societies told themselves, on one level a group of signs conveying a surface-level meaning, but on several deeper levels imparting things like values, basic behaviors, and foundational beliefs that made a society possible. He and Strauss investigated many different societies and found that although no two societies were directly comparable, even so-called “primitive” hunter-gatherer societies had certain familial resemblances to modern European, particularly French society, such as our use of binary oppositions in identity to make society function.

Enter the young Gilles Deleuze, who sees that, up until now, the history of philosophy has been one of defining things according to binary oppositions: a thing is what it is, and it is not what it is not. You can see this in examples like Being versus Non-Being in Heidegger, or good versus evil in Moore, rationalism versus empiricism in the history of philosophy, and so on. Like the process philosophers in English, however, Deleuze finds identity incredibly hard to nail down this way because the binary oppositions only arise if we take a temporal slice of an idea. Ideas, concepts, and the like are constantly growing, evolving, and changing as human thought changes. They are not static, but our metaphysics and ontology until this point have only been able to define things in stasis.

So Deleuze develops this metaphysics of difference. Rather than difference being derivative of and secondary to identity, Deleuze inverts the relation: we identify things by differentiating them. And it this insight that leads Guattari and Deleuze to attempt to approach the central problems of the world in the late 60s/early 70s: capitalism and mass media culture.

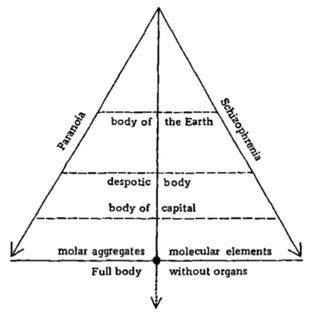

Guattari in particular wishes to respond to and grow beyond Freud and Lacan in psychoanalysis. He sees the benefit of it in his clinical practice, but also has found it limiting in some ways, the same way Deleuze found the metaphysics of identity limiting. And so they start from this position that both Freud and Marx are wrong, but that certain key insights can be salvaged, and, if married to the concept of difference, we can redefine metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, ethics, and media theory in such a way that we produce an entirely new way of thinking, modeled after schizophrenia, a kind of earnest delirium in which we reclaim and restructure experience and logic in ways that are freer, more creative, and not bound by the historical binary oppositions of the past.

They do not mean that we must literally adopt the thought-patterns and worldview of the schizophrenic. Rather, they see something as liberatory in that kind of free thinking, and hope that by the end of their project, we can find a way to incorporate that kind of freedom into our thoughts, but in a way that provides a new way of thinking and doing politics and culture. They call this method “schizoanalysis.”

And if you try to read Anti-Oedipus, you are going to encounter a dense, frustrating, and in many ways incomprehensible text, because not only is it meant to be an academic explanation of schizoanalysis and philosophy, it is meant to be an example of the text itself. So as you learn the method, you are also reading a product of the method. It is antithetical to the foundational way that education is presented, and that is what makes it difficult to describe. Imagine having to learn a new language only by reading texts in the new language without the benefit of any translations or reference.

So, this brings us to the first part of explaining just what is going on. I caution you, this is probably not going to make sense until about halfway through the series. I just ask you right now to shut off your mental filters and just absorb everything I am telling you. Do not try to think through it or try to understand. Be like a sponge and just soak up this background.

The first two concepts we have to understand are machines and desire. Let’s take them in stride.

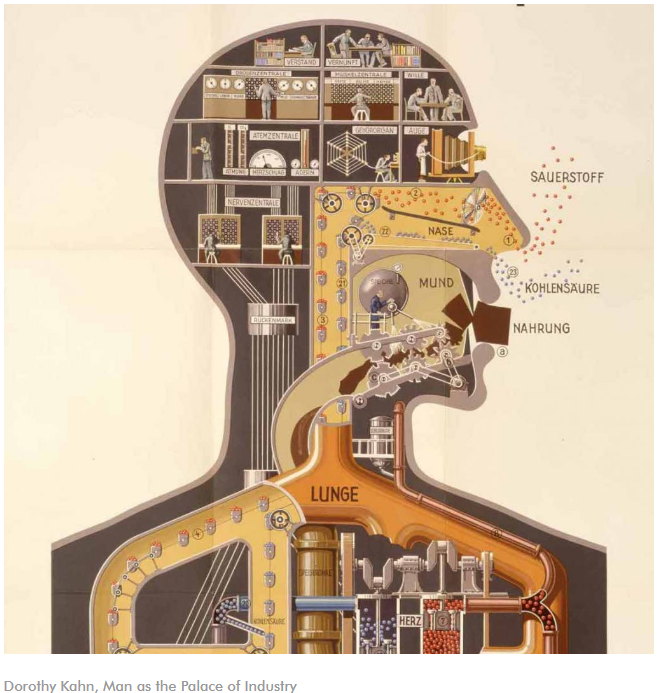

Famously, Anti-Oedipus declares that “everything is a machine.” Rather than being rhetorical flourish or hyperbole, this is instead a statement of the radical new ontology D&G are describing. They mean this quite literally: in schizoanalysis, the machine is the basic ontological unit, not being, not objects or subjects, but machines.

A machine in this sense is anything that does something; all machines exist to fulfill some function, and are defined by their operation to fulfill this function. Machines are dynamic and iteratable: a machine can be a part of another machine and so on. This is in many ways a psychoanalytic concept: machines work without conscious guidance, much like drives in psychoanalysis. You are a complex of different machines, all working together. The national economy is a type of machine made up of tens of thousands of other machines. Think of a machine as any “machinic” process, that is, anything that is designed to accomplish a given task. They are not really definable in the sense of a term you can grasp; machines are what they do, but take this as our basic ontological unit. The entire world is made up of millions of these goal-directed processes operating, interrupting each other, finishing, restarting, etc., at any given time. The world is constant dynamism.

Desire, on the other hand, is easier to pin down, because it involves a binary opposition. See, rather than stop using such oppositions altogether, D&G instead employ them as one tool among many for understanding the world. This is one way in which they escape the dialecticism of Hegel or Marx: they do not seek to supplant an earlier theory or merely grow beyond it, but to grow around it and subsume it like a fungus might subsume another organism, incorporating it within its own structure.

So even as machinic ontology begins to draw us away from structuralism and its focus on signs and meanings, Deleuze and Guattari come right out and say that the Freudian/Lacanian concept of desire is wrong. Psychoanalysis sees desire as a lack, that is, the subject orients itself toward the object of its desire by saying, “I lack this, therefore I want it.”

For D&G, on the other hand, desire is a real and productive force. It is more akin to something like Nietzsche’s will to power or a general will to live. Desire is the motive force that gives machines their fuel. This leads to what they term as “desiring-production,” or an explanation of how machines are going to interact with later concepts in their theory like hylë/flows and coding/decoding.

For now, the important part to understand is that we must jettison the metaphysics of stasis and identity for one of dynamism. Nothing is what it is; things are instead made up of what they do (often many such things) that are motivated by this very real and motive force called “desire” that is not simply about obtaining what one wants but to possess, subsume, and integrate that into the thing itself. The entire operation of these two concepts creates the desiring-production, or a sort of social cosmology of everything about the world, from basic needs on up to the highest expressions of mass culture. And you can see this represented in everything not only from society but also nature.

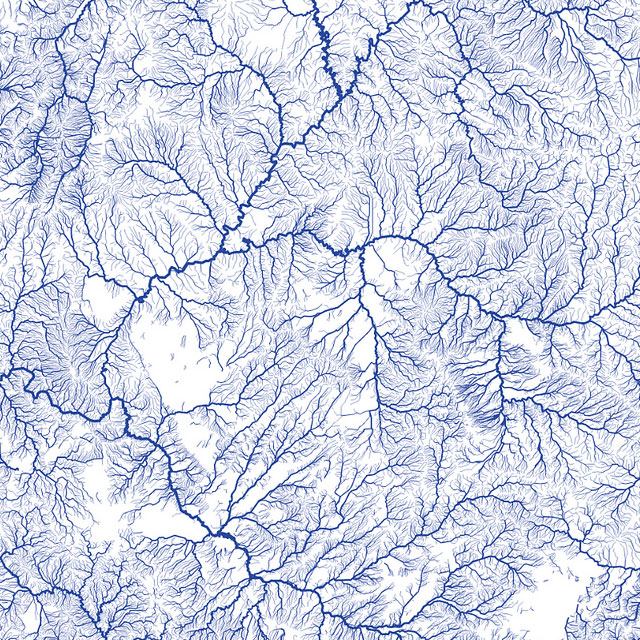

Have you ever looked at a map of the blood vessels and capillaries in a human body? Have you ever looked at map of just rivers, creeks, and drainage basins on a continent? Don’t they look similar? What about the bare branches of a tree in winter? Starting to see these same patterns that appear at first chaotic? But are they really chaotic if the same general structure repeats over and over again throughout nature? Is that not some evidence that these patterns and structures are not only immanent but somehow also transcendent? And if so, why?

The reason, D&G want you to realize, is that the underlying machinic processes that give rise to human consciousness at all are the same processes that carve canyons out of rock or write symphonies or govern sewage systems or define entire systems of economic production: machines and desire.

So if you’ve come with me this far, this ends lesson one about machines and desires. Go out and look at the world, and tell me if you cannot see the machinic activity powered by desire.

Next time, we are going to go over flows and rhizomes.